published in Vogue October 2013

|

| photo Wayne Maser, Vogue, 1988 |

Today I am going to the John Marshall studios on Ninth Avenue between Forty-fourth and Forty-fifth streets to hear Meg Ryan record the audiobook of Sister, Mother, Husband, Dog (etc.). I am anxious—anxious because writing this book was deeply emotional for me. I am worried that, in that studio, I am going to fall to pieces.

I began this collection of essays in the months after my sister's death. Writing is how I understand everything that happens to me, and it became the way I got through the days, processed my grief I guess you could say, writing every afternoon about Nora and me, about sisters, in my tiny office, which has room only for a desk and desk chair, one narrow bookshelf, and, in the corner, a small tufted white armchair that Nora gave me when she no longer needed it. "I have two tufted armchairs and a love seat, do you want them?" she had e-mailed.

Nora is everywhere in my office. On the wall above my desk hangs a prop from You've Got Mail, which we wrote together—the sign from Meg's children's bookstore, the Shop Around the Corner. On a shelf is a miniature tin school bus encased in a clear plastic cube, a gift from Sean Daniel, the producer of our movie Michael. It commemorates a mini battle Sean and I waged against Nora. We begged her not to cut a scene early in the movie involving a school bus and children dressed as Eskimos. We argued that it was funny and we needed something funny up front. We won. A triumph. Getting Nora to change her mind was like trying to reverse a very strong current. On the top shelf is a portrait, by that I mean taken by someone my parents hired to photograph Nora, me, and my sister Hallie. We are eight, five, and one-and-a-half, respectively, and all dressed up, Nora and I in matching black velvet dresses with a white ruffle around the bib collar, Hallie in a crisply ironed white cotton dress with smocking. Being used as a paperweight is a framed four-by-six snapshot of Nora, my sister Amy, and me in the Las Vegas airport when Nora and I were shooting This Is My Life, the first movie we wrote together and she directed. Nora and Amy look fabulous, and I have the worst haircut of my life, which is why this photo is lying fiat (and not standing up so I can see it). On the wall next to the door is a most prized possession, a poster of Love, Loss, and What I Wore, our last collaboration, signed by all 120 women who performed the play in New York. And on the desk right behind my computer, next to a photo of my husband eating a liégeois (sundae) in Paris, is another prized possession: a vintage postcard that Nora gave me one Christmas. Sprays of violet flowers entwined with these words: TO MY DEAR SISTER. The word sister is studded with forget-me-nots.

Never in my life did I expect to be writing about losing Nora. I never expected to spend one day on this earth without her. And I certainly never expected to be in a recording studio listening to Meg Ryan speak those words. Our collaboration—Nora's, Meg's, and mine—was a threesome. Now we were two.

Meg, of course, teamed up with Nora first in When Harry Met Sally, which Nora wrote. I joined their sisterhood on Sleepless in Seattle and You've Got Mail. Then Meg starred in Hanging Up, a movie based on my autobiographical first novel. Meg played Eve, my alter ego, a middle child dealing with the death of a difficult parent. My cinematic life, my identity even, has been tangled up happily with Meg's.

I had been nervous to ask Meg to record my memoir, in which I eventually pondered not only my life with Nora but with my other major food groups—mother, husband, girlfriends, dog. I was nervous because I desperately wanted her to say yes. No one could do it better. I spent at least a day boring several close friends with my anxieties about the best way to go about it—what words might be exactly right. In the end I wrote a cautious, tentative e-mail: "Is there any possibility that you might consider... ?"And she wrote back instantly, "I'm in!"

On the ride uptown, I am wired, so fearful of emotions about to be unleashed that I almost trip over my own umbrella getting out of the cab. Then, a shock, I spy Westway, a Greek diner, and realize something that should have been obvious: This recording studio is one-and-a-half short blocks north of the theater where Love, Loss played. I haven't been here since the play closed in March 2012, three months before my sister died. We spent more time together in this neighborhood than anyplace else, except perhaps our apartments.

Meg has already begun recording when I arrive. She is in the "isolation booth" and leans sideway to give me a wave through the thick glass. Laura Grafton, the director from Brilliance Audio books, tells me that Meg asked to start with the lighter, funnier essays, which means not the one about my mother and:for sure, not the remembrances of Nora. I am relieved. I need to start with the lighter stuff, too. I settle in next to Laura at the long table, open my manuscript, and am immediately sucked into the work. Getting the flow, the drama, the comedy, the emotion, the overall sense of it, and word perfect...nailing all that in two days with no rehearsal, it is suddenly clear, will not only be completely absorbing but also possibly a bitch.

On a break—and you have to break every hour or so or your brain will fry—Meg comes out to give me a hug. What I most associate with Meg—the way I remember her and recognize her when I see her again—is the way she moves. Her tomboy walk—her lanky, easy physicality so much a part of her comedic gifts. She is playful and loves to laugh. I imagine she wakes up every morning and thinks, What am I going to laugh about today? She has a great appreciation for what in this world is nuts.

Also, she has a glow. Stars do. Did they always have it, did they learn it? And why are they always wearing the best clothes even when they're not? These are mysteries. Reed thin, she is in a black-and-white striped T-shirt, dungarees, and a wide leather belt. Her hair, short, is an adorable mess—bedheady. She looks fantastic.

At lunch we talk about random stuff—Meg's kids, Laura's daughter, Anthony Weiner's catastrophe of a life. The day flies by, and at 4:30 we are all exhausted and only one-third done. We are supposed to finish the next day. We agree to meet earlier, at nine, and work later, until five.

The next morning, in honor of my sister and all the meals we've eaten together, discussed before we ate, while we ate, and after we ate, and how well she always took care of the cast and crew food-wise (we had the best catering), I stop at Bien Cuit, a divine bakery, and buy for Meg, Laura, and our wonderful audio engineer Nathan Rosborough two raisin and-walnut rolls; four chocolate-chip shortbread cookies; four small, round, dense chocolate cookies; four malted muesli cookies; two strawberry-and-rhubarb Danishes; one brie-and ham croissant; and one chocolate croissant.

In spite of this bakery detour, I am early. I pick up a takeout menu from Westway. I want to order their tunafish sandwich for lunch. This was our hangout. The cast of Love, Loss changed every four weeks, and during the first six months, Nora and I attended most of the rehearsals. At lunch all of us, the cast and our director, Karen Carpenter, went to Westway and crammed ourselves into one too-small booth.

At Forty-third Street I turn right to visit the theater. I remember the first day of rehearsal with our very first cast. We were sitting on the stage at folding tables arranged in the shape of a square. There were eight of us, some old friends—Rosie O'Donnell, who had been in Sleepless, and Katie Finneran, who had played nanny Maureen in You've Got Mail, and has since won two Tonys, and is now starring in the new Michael J. Fox series—and some actors that we were just getting to know: Tyne Daly, Samantha Bee, and Natasha Lyonne (who is a smash now in Orange Is the New Black).Our director was there, and everyone was talking the way women do, yakking and laughing about God knows what, and I, always the anxious sister, whispered to Nora, "We better start rehearsing or we'll never have time to finish," and she whispered back, "This is rehearsal."

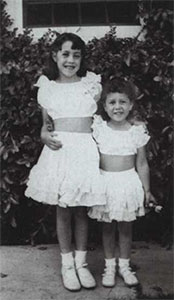

|

| TWIN SET Nora (left), age 7, and Delia (right), age 4, in their Beverly Hills backyard. |

My sister was always teaching me important things in an offhanded way. Obvious things, too. How did I not know this? My entire professional life flashed before me—all the times I had walked into a meeting and waited for the meeting to start—waited for the chitchat to be over, to get to the point, for the moment for me to state my intent. In fact the meeting had started the second I walked in the door. Of course rehearsals should begin with bonding, especially rehearsals for a play about women and clothes, but all work/meetings/adventures should begin ideally with the possibility of friendship, and in the case of women, maybe even sisterhood.

Old Jews Telling Jokes is playing at the theater now, its banner hanging from the same pole ours did. Directly across the street is Esca, a chic fish restaurant, where Nora was always trying and failing to convince me to order spaghetti with sea urchin. On opening night we sat at the bar there, too nervous to sit in the theater and watch, returning just before curtain.

It was almost time to start now, so I headed back to the recording studio. After rehearsals Nora and I always walked together from the theater to the comer of Forty-third and Ninth, rehashing the day, discussing whether parts were properly assigned, what bits needed fixing, what notes might help actors. Then Nora caught a cab and headed uptown, and I took one downtown or else walked over to the subway at Times Square. On this comer I have so many memories of us saying goodbye.

After that walk, it is no surprise that I arrive at the studio again primed for tears. But there is so much to accomplish. With no fuss, no sentimentality, Meg dives into the heavy stuff.

My favorite part of making movies is the "table read." Before a movie begins shooting, all the actors sit around a table and read the script aloud. It is helpful—weaknesses and strengths pop right out-but it also showcases the incredible talent of actors minus all the "stuff"—costumes, makeup, close-ups, action. No rehearsal even. I love the purity of it. The words shine. And that's what Meg has been treating me to these two days. Truth be told, as emotional as this is, as burdened with loss and love, I am having the best time.

Why did I expect to fall to pieces?

Was it simply inevitable that I would fear this?

One day, during the last weeks of my sister's life, I arrived at the hospital as I did every morning and realized that I had left my cell phone in the taxi. It had no security code and contained many text messages—medical updates to other family members, cryptic but nevertheless the meanings were clear.

In an instant my heart threatened to pound out of my chest, my clothes soaked through. The next passenger would find my phone, I was sure, and figure out everything. After six years of keeping the secret of my sister's illness, I would be the one to let it out. I would betray her.

I was so panic-stricken, I truly almost lost my mind. My meltdown lasted at least a half an hour—it felt like forever—and then I found my phone. I had had it all the time. It was in a zippered compartment inside another zippered compartment (extra safe, in fact) of this insane MZ Wallace bag that has a pouch for everything, a nightmare for me because I never put anything in the same place twice.

At the time I put the panic attack down to stress, worry, anxiety. But now, looking back, I think, to put it mildly, more was going on. My meltdown was cosmic, the cause imaginary, which makes me think that guilt, not stress, fueled it. My betrayal was much greater than outing her illness. It was that I would be able to do wonderful things like this—collaborate with Meg, work together creatively the way the three of us had. That was the real betrayal—that I would live on.

Hard to admit.

So hard to admit and painful that I think I couldn't face it. Instead, in anticipating this taping, I sort of flipped it around in my mind, telling myself that I would fall to pieces when what I was much more worried about was what actually happened: I would enjoy it.

So hard to admit and painful that I think I couldn't face it. Instead, in anticipating this taping, I sort of flipped it around in my mind, telling myself that I would fall to pieces when what I was much more worried about was what actually happened: I would enjoy it.

We had a joyous time that day, although the work was so intense that Meg said she felt as if her eyes and mouth had separated from her face and would no longer work together. We ate almost all the pastries and a bag of Utz potato chips. We met again the next morning for another three hours before staggering home.

Did I have all the fun I could? Did I work hard enough? Did I remember to tell Meg everything I needed to tell her? Did I thank everyone enough? Did I feed everyone enough? Did I honor my sister in all those ways? And in the book itself? Or is it only my standards I have to live up to now?

The next morning, after sleeping a good ten hours, I woke up with a weight on my heart. Not wanting to get up. Wishing I could call Nora to rehash it the way we always did after rehearsals or long hours on set. Those three days went by so fast. So fast. Like life.